Red flag or red herring? Here's how AI’s power, water and carbon footprints stack up on a global scale

Keep calm and count the kilowatts

Part one of our Keep Calm and Count the Kilowatts series showed how AI prompts are only a small portion of a person's daily power use. But with OpenAI alone now handling over 2.5 billion prompts a day from hundreds of millions of active users, how does the power use look on a global scale?

The big picture

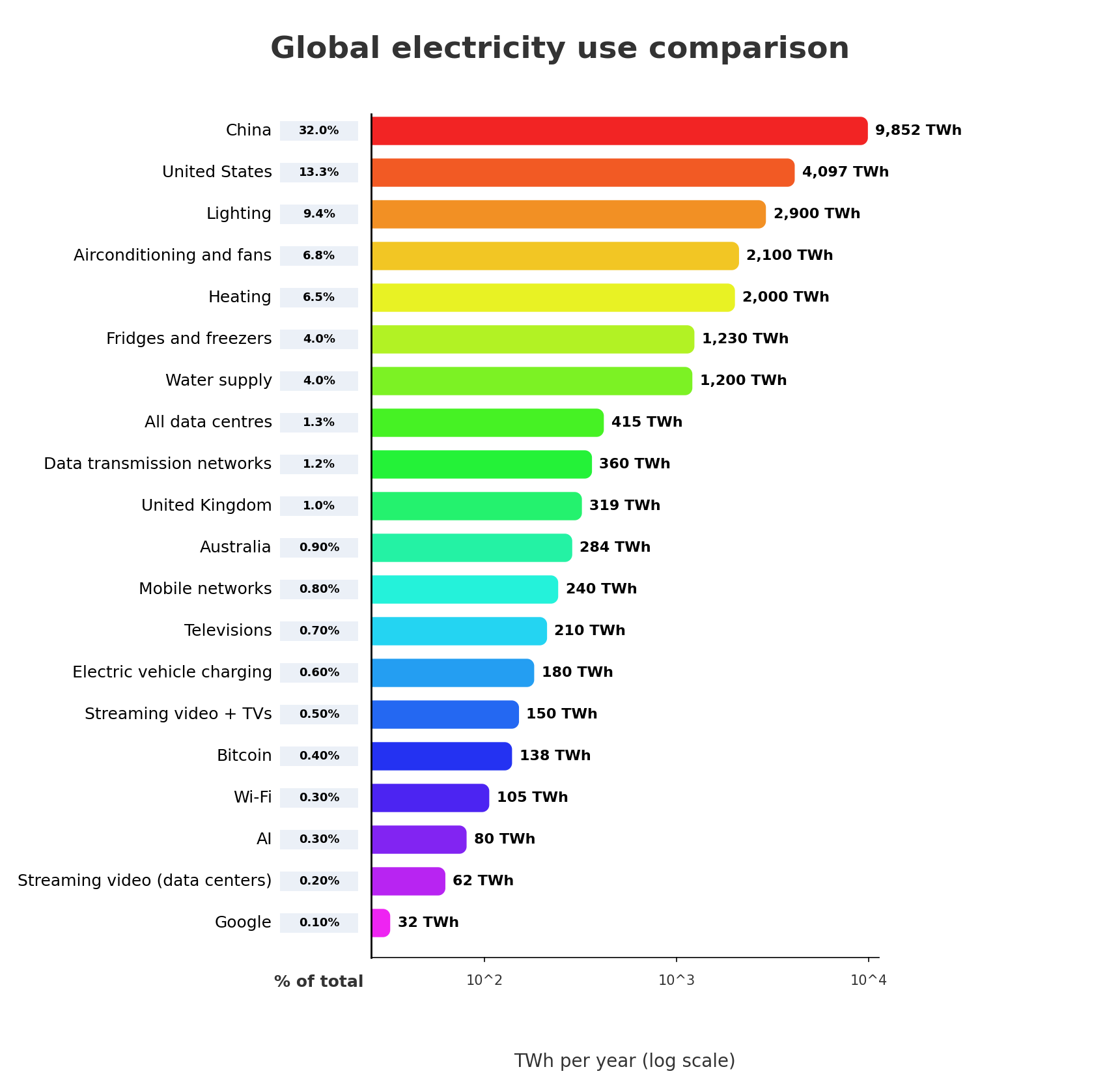

Looking at the total context is where doom and gloom articles often miss explaining how AI fits into global resource use. So for an easy comparison, I’ve collected together the annual power use for a range of relevant and interesting uses and categories.

It’s pretty clear that AI is a tiny fraction of overall electricity use on a personal or global level and it’s beaten by tech as unassuming as Wi-Fi. That doesn't mean it's not still a huge amount of power – if Wi-Fi was a country, its electricity use would rank it in the top 50.

AI is also going through a period of very rapid growth, which is normal for transformative new technology. Take televisions for example – by the 1980s, they were consuming similar amounts of electricity to AI today.

In fact, the electricity consumed by the average TV-watching family in the 80s was comparable, on a per-person basis, to the power needed for all the world's data centers today.

AI may be a new rising star, but it’s still only 10% to 20% of the 415 TWh a year of power used by data centers overall. Over 50% is for enterprise and government use (think corporate cloud storage, online banking, and digital government services), while streaming video takes about 15% and the 10 trillion+ smartphone pics in the cloud (3 trillion of those are my dog in slightly different poses) are about 0.2%.

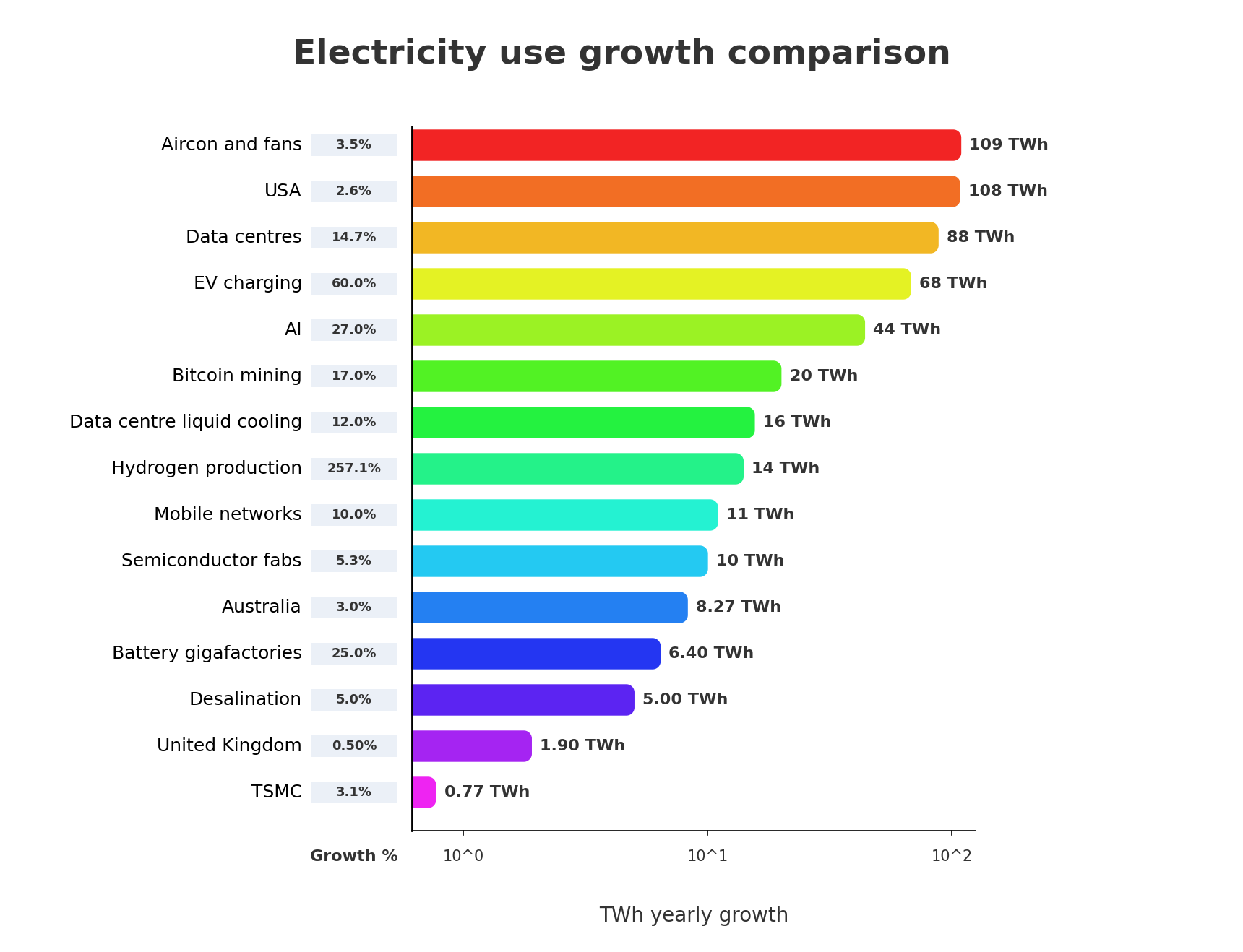

The overall growth is not slowing down either and data center power use is expected to double by the end of the decade, with a significant chunk of demand driven by AI. It’s hard to know what the future will hold, but even if AI is the majority of data center electricity use, it’s still only a small part of worldwide use.

Of course, AI is not the only tech going through massive growth right now and power hungry 5G cellular may soon catch up. Electric vehicles are one of the fastest growing new users of electricity and will easily top out at 100x as much power compared to what AI uses today.

What about water and CO2 emissions?

It's easy to get focused on electricity and forget that there are other resources, and pollution, in play.

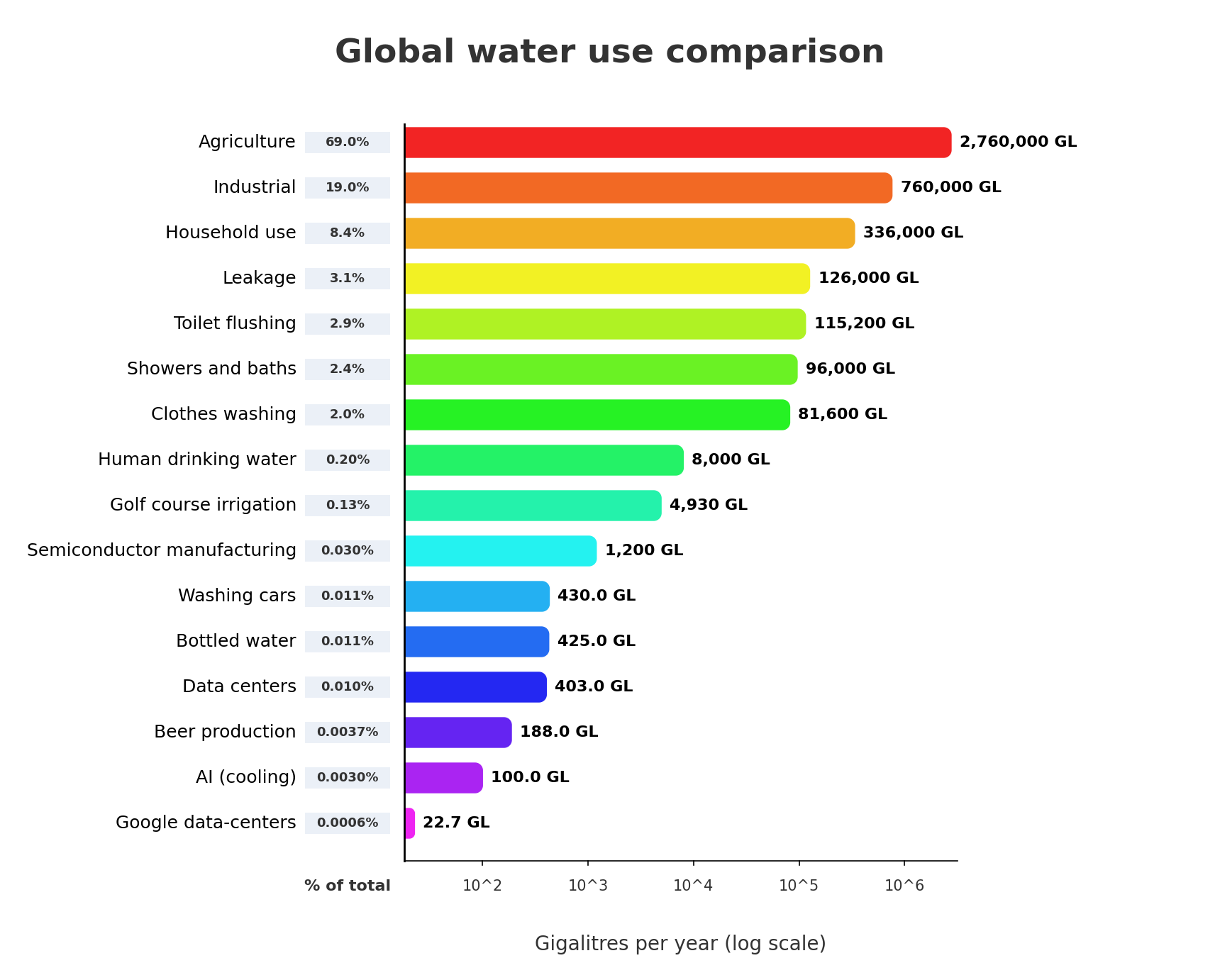

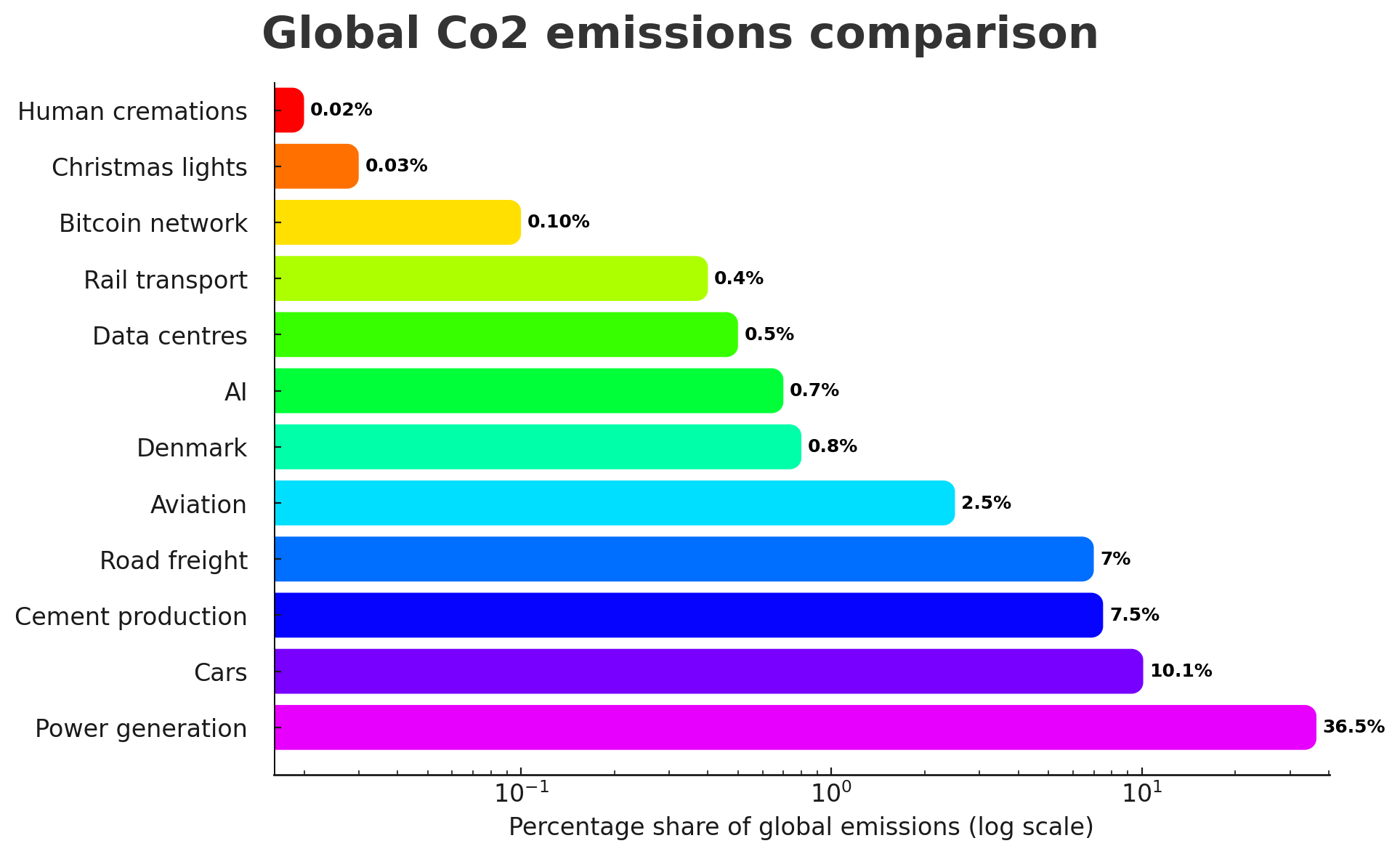

While data centers don't emit CO2 directly, often the electricity used is from fossil fuel power generation, so they have an associated amount of CO2 released. Water is also used for boosting the cooling systems of data centers (and not just for AI), as well as for cooling in power generation. While the water is not consumed (it evaporates and returns as rain), it's still removed from the local environment.

So how do these resources used and CO2 emissions stack up? Depending on which end of the scale you look at it from, broader AI resource use is both tiny, yet huge.

For example, the full flush once you are done reading this article could provide cooling for 10 prompts a day for almost 5 years, and one 500 ml disposable bottle of water can provide cooling for 2,000 prompts.

In total, 100 GL of water goes to cooling AI in data centers each year, which is about the same as what’s wasted by automatic watering systems making golf course extra wet while it's raining.

That's not to say 100 GL isn't a lot, and it's enough to fill 40,000 Olympic swimming pools and is a critical resource in many areas. But it's also only about 0.003% of the world's total yearly water use.

We obviously shouldn't be wasting water, but data centers (and AI) are arguably pretty far down the list of usage we should be most concerned about.

Then there’s the carbon footprint. 0.03 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per prompt, which is about the same as you exhale in one breath. 10 prompts a day are equal to the CO2 emissions from the candle at a one-year-old’s birthday party or idling your car for less than a second.

Or, for a more universally understood unit of measurement that I totally didn't just make up, 58 million prompts per Zamboni® year*.

All up, the yearly emissions equivalent from AI power use is around 0.07% of the global total. Looking at the big picture, that’s a tiny fraction – about the same as the ridesharing industry.

But 0.07% of a very very large number is still a lot of CO2 and puts AI on par with the entire country of Denmark. That’s not great.

Disproportionate effects

The real environmental story of AI isn't the tiny sip of power your individual prompt uses; it's the massive, concentrated impact of new data centers on the specific towns and ecosystems they're built in.

But more on that in part three of Keep calm and count the kilowatts series – The disproportionate effects of AI data centers on local communities.

Not convinced Zamboni® year is a valid measurement of CO2 output? Drop the mitts and let’s dance in the comments!

AI skeptics might also like

- Companies are using more AI than ever - and many are happy to turn a blind eye to its environmental impact

- Sam Altman thinks ChatGPT’s energy usage is nothing to worry about, but is he right?

- Google's data centers using more power than ever before as AI surge continues

AI enthusiasts might also like

- Google is spending $3bn on renewable power for its data centers

- Data centers are transforming waste heat into community energy assets

- Google says it will switch off energy-heavy AI usage at critical points if needed

- Robots that can automatically refill liquid cooling systems unveiled at OCP Summit - and yes, that sort of has Matrix vibes to it

How we use AI

Here at TechRadar, our coverage is author-driven. AI helps with searching sources, research, fact-checking, plus spelling and grammar suggestions. A human still checks every figure, source and word before anything goes live. Occasionally we use it for important work like adding dinosaurs to colleagues’ photos. For the full rundown, see our Future and AI page.

Zamboni® year calculations

One Zamboni® year = the CO2 output of a single Zamboni® brand ice resurfacer per year. How did I calculate this? Fairly inaccurately.

Note: Frank J. Zamboni & Co. is proactive about protecting their trademark on the Zamboni® name, to avoid it becoming a generic term. In fact, Zamboni® is a registered trademark of Frank J. Zamboni & Co., Inc. Thus the Zamboni® year focuses purely on Zamboni® ice resurfacing machines, with an impressive 12,000+ produced since 1949!

The International Ice Hockey Federation lists over 8000 rinks worldwide, but there are likely hundreds more not listed. Larger rinks use two machines but very few have none, giving around 11,000 in operation. A sum of resurfacing times, rink operation days and so on gives an estimate of around 650 hours of use per machine.

Most run on propane, and ~20% are electric, which gives about 95 kilotons of CO2 emitted per year for all ice resurfacing machines (including CO2 emitted for electricity generation). This is about the same as emitted by birthday candles.

Divided by 11,000 ice resurfacers, that's an average of 8.6 kilotons of CO2 each per year. According to Popular Mechanics, 58% of ice resurfacers globally are made by Frank J. Zamboni & Co., which means around 58 million prompts are the equivalent to one year of average Zamboni® ice resurfacing machine CO2 output.

Disclaimer: there are enough approximations here that the result has a very high +/- error, plus it changes over time due to electric adoption, so it's absolutely not a good unit of measurement for comparing CO2 emissions.

Lindsay is an Australian tech journalist who loves nothing more than rigorous product testing and benchmarking. He is especially passionate about portable computing, doing deep dives into the USB-C specification or getting hands on with energy storage, from power banks to off grid systems. In his spare time Lindsay is usually found tinkering with an endless array of projects or exploring the many waterways around Sydney.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.